Material Culture and Cultural Practices

Explore the sections below to learn more about the material culture and cultural practices shown in the Lucayan Lifeways illustrations, and the evidence on which they are based.

Baskets

Image credit: Mat-impressed ceramic sherd, the fibres of the palm fronds still visible. Courtesy, National Museum of The Bahamas (AMMC)/Gerace Research Centre, San Salvador.

Unfortunately, no Lucayan baskets have survived in the archaeological record, but impressions of their patterns and textures have been recorded on ceramics which, when wet, were likely left to dry on basketry mats. The varied weaves recorded in clay suggest that there were numerous basketry patterns.

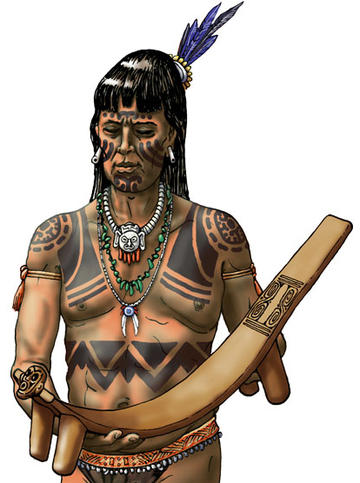

Body painting

Image credit: © Merald Clark, for SIBA: Stone interchanges in the Bahama Archipelago, 'Cacique and Emissary'

Columbus’ (in Keen 1992:60) first descriptions of the Lucayans included mention of body painting: “… they were of middle stature, well formed and sturdy, with olive-colored skins that give them the appearance of Canary Islanders or sunburnt peasants. Some were painted black, others white, and still others red; some painted only the face, others the whole body, and others only the eyes are nose.”

The body was viewed as a canvas to adorn with colour and designs – something to be seen and visually appreciated, but also something that may have had practical as well as spiritual meanings.

Covering the body with a thick layer of pigment added a level of protection against the intense tropical sun, or helped against the sting of insects.

Specific designs, their combinations and alignments, may have added spiritual protection.

Canoes

Courtesy, The National Museum of The Bahamas (Antiquities, Monuments and Museums Corporation), Nassau, The Bahamas.

Canoa is a Taíno word that has remained with us to this day as a term for small, paddled watercraft.

Columbus described Lucayan canoes as “…made from the bole of a tree hollowed out like a trough, all in one piece. The larger ones hold forty to forty-five persons; the smaller ones are of all sizes, down to one holding but a single man. The Indians row with paddles like baker’s peels or those used in dressing hemp. But their paddles are not attached to the sides of the boat as ours are; they dip them in the water and pull back with a strong stroke. So light and skilfully made are these canoes that if one overturns, the Indian rowers immediately begin to swim and right it and shake the canoe from side to side like a weaver’s shuttle until it is more than half empty, bailing out the rest of the water with gourds that they carry for this purpose.”

The only surviving Lucayan canoe was recovered from Stargate Blue Hole, Andros in fragments, and is estimated to have had a length of about 2m. This image shows the prow of the Stargate canoe. For a reconstructed view see https://siba.web.ox.ac.uk/iconography-archipelago

Ceramic Imports

Image credit: Three ceramic vessels from the Dominican Republic. Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, 010152.000; 059303.000; 197733.000

Many sites within the archipelago feature both local (Palmetto Ware) and imported (Chican Ostionoid or Meillacan Ostinoid) ceramics. The Lucayans enjoyed using imported ceramics, which were prized for their durability and beauty, their rims ornamented with two-dimensional designs and their handles in the shape of animal and human heads.

Dogs

Image credit: © Merald Clark, for SIBA: Stone interchanges in the Bahama Archipelago.

The Lucayans had dogs as pets, and to assist with hunting hutia (rodents, Geocapromys ingrahami). They were originally imported into the Bahamas when people migrated from the larger Caribbean islands in the south; dogs travelled with their human companions in their canoes.

Their history in the Caribbean goes back at least 2500 years, when dogs accompanied people migrating from South America into the Lesser Antilles.

Dog burials, often associated with human burials, have been found across the Caribbean. Two types of dogs were present in the region: a small dog, sometimes used as food, and a larger dog which was a pet and hunting dog (which the Taíno called aon).

Dog remains have been found at the archaeological sites on Middle Caicos, TCI and Long Island, Bahamas. Drilled dog teeth have been recovered from Long Island; they were most likely used as pendants, possibly in remembrance of a much-loved pet and/or a prized hunting dog

Dogs are featured, though rarely, in Lucayan art – such as the dog-headed duho recovered from Cartwright Cave, Long Island.

Hafted axe

Image credit: Hafted Axed. L: 55.5cm. Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, 06000.000.

Hafted axes were essential woodworking tools. Consisting of a hardwood handle to which a polished stone or shell blade was secured with cordage and gums, the hafted axe would be used to fell a tree and to block out the shape of the object, whether a canoe or a carving. Stone celts of jadeite, basalt or other hard stones, had to be imported into the limestone archipelago. This hafted club was found in a cave on North Caicos, TCI during commercial guano mining; it is carved from Guaiacum (Guaiacum sp.) and has been radiocarbon dated to calAD 1029-1160 (95.4%).

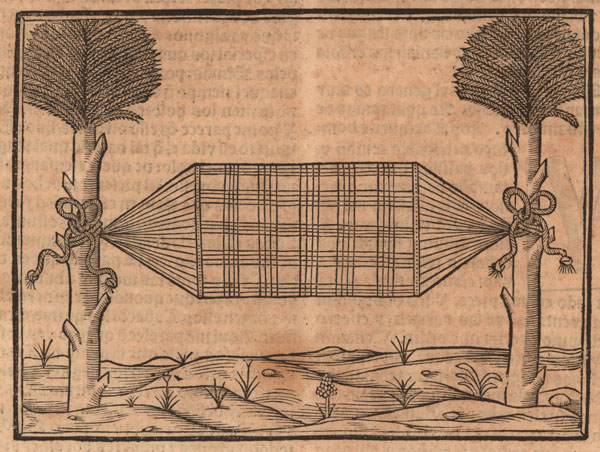

Hammocks

Image credit: A 16th century illustration of a native (Taíno) hammock from Hispaniola (today’s Dominican Republic and Haiti). Detail from Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1547, Historia general y natural de las Indias. ©John Carter Brown Library, Acc. No. 01632, verso of leaf xlvii [47].

During his visit to Long Island, The Bahamas, on 17 October 1492, Columbus and his men saw hammocks for the first time. He writes:“… their beds and hangings were things that are like cotton nets.” The term hammock is a Taíno/Arawak word. Suspended between two points, these convenient beds raised those resting in them above the ground, away from biting insects or snakes, enabling a safer and more comfortable sleep.

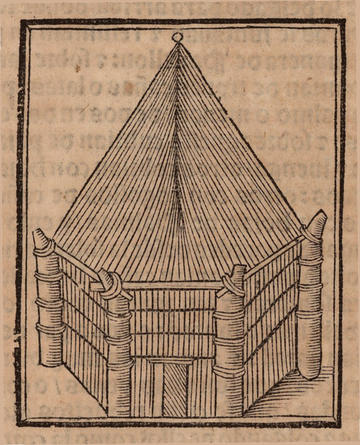

Houses

Image credit: A 16th century illustration of a native (Taíno) house on Hispaniola (today’s Dominican Republic and Haiti). Detail from Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1547, Historia general y natural de las Indias. ©John Carter Brown Library, Acc. No. 01632, verso of leaf Iviii [58].

Lucayan houses, as Columbus describes them, resembled “Moorish tents,” suggesting a round building with a conical roof. On Long Island, Columbus’s men visited a village of 12-15 houses. Among the neighbouring Taíno, this type of structure is known as a bohio and likely housed an extended family (possibly up to 15 people).

Hutia

Image credit: © Merald Clark, for SIBA: Stone interchanges in the Bahama Archipelago.

Hutias (Geocapromys ingrahami) are large rodents endemic to The Bahamas, but not the Turks and Caicos, where they must have been introduced by settlers; the evidence from such sites as Palmetto Junction, Providenciales, suggests that they were part of interaction and mobility networks.

As shown in “Journey’s End”, they are part of the cargo being brought to the Lucayan archipelago, in efforts to replenish the stock. It is possible that they were bred in captivity and potentially domesticated, as has been suggested for Cuba.

Paddles

Image credit: Two views of a paddle recovered from Mores Island, The Bahamas in 1912. L: 129 cm; (blade length: 63.5 cm). Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, 033574.000.

As sea-faring people, the Lucayans knew the value of a well-made paddle (nahe). The blade had to cut efficiently through water, lending leverage and speed to powerful strokes. Paddles were a marriage of function and aesthetics.

This example, one of a rare few to survive in the region, has a simple, geometric design on its upper blade. Found in a cave on the northern island of Mores, neighbouring Abaco, it is carved from mahogany (Swietenia sp.) and has been radiocarbon dated to calAD 1436-1616 (95.4%).

Palmetto Ware

Image credit: Reconstructed ceramic vessel with zoomorphic lugs, San Salvador, Gerace Research Centre, San Salvador (AMMC). Reconstruction: Ostapkowicz.

Within The Bahamas/TCI, locally produced ceramics are known today as Palmetto Ware. The earliest examples of Palmetto Ware were recovered from the Three Dog site on San Salvador, dating to ca. AD 800, and the pottery style was still in use when Columbus arrived in the region. Palmetto ceramics are an important marker of adaptation to the Lucayan environment, using locally available red loam and clays combined with burned and crushed shell as temper. This shows that local settlers were utilising the resources around them, rather than relying on imported products (though no doubt traded wares were appreciated not only for their durability and aesthetics, but also for the links they helped maintain with the larger southern islands). A variety of Palmetto styles are now recognised – including Abaco Red Ware and Crooked Island Ware.

Complete ceramics are rarely recovered, largely because they are relatively fragile. But occasionally, larger sized fragments enable a reconstruction of the size and shape of the original vessel. In the reconstruction featured here, the original bowl would have measured some 60cm in length. Such sizes were likely made for large communal gatherings and feasts.

Parrots

Image credit: © Merald Clark, for SIBA: Stone interchanges in the Bahama Archipelago.

Parrots were offered in trade to Columbus and his men during their voyage through the archipelago in October 1492, which suggests that they were actively traded as pets and for their feathers.

The Taíno word for parrots was guacamayas, the prefix ‘gua’ is linked to the word guanin (a gold/copper alloy) and to important cacique (chief) names, such as Guacanagari – linking bright, precious objects and animals with power and status.

Parrot feathers were undoubtedly used for body ornaments - woven in hair, worn as part of ear and neck ornaments and added to the tassels of cotton arm/leg bands or naguas and belts. Early accounts from Jamaica mention caps and even capes made out of feathers.

Parrots were likely domesticated from hatchlings, when they are easily trained; they generaly make for excellent, intelligent and affectionate companions.

Columbus writes that flocks of parrots would darken the sky; they are now endangered due to habitat loss and other threats (predation by wild cats, boars, etc.; pet trade), with only two populations on Abaco and Great Inagua and a very small group (ca. 10 individuals) on New Providence.

Shell beads

Image credit: Shell beads in the process of manufacture, Pink Wall, New Providence. Courtesy, The National Museum of The Bahamas (Antiquities, Monuments and Museums Corporation), Nassau, Bahamas. AMMC, NP12-171-3.

The Lucayans prized shell beads for their colour, beauty and lustre. They were made for trade, and would be worn strung on cords as necklaces or woven into belts or naguas (a short skirt worn by women). Beads recovered from the site of NP12 (New Providence), show the techniques used in their manufacture:

1. the smooth white shell disk in the upper right has an indent from a drill bit, but for some reason work on it stopped before the drill perforated the shell.

2. the large white bead on the upper left, shows the disk perforated, but before the final reworking – the outer edges are still rough and unpolished.

3. the small red bead shows the finished product, with the outer edges polished down to a narrow ridge. These tiny beads would be incorporated into beautiful ornaments.

Spear

Image credit: worked stingray spine, possibly used as a spear tip. Gordon Hill site, Crooked Island. Peabody Museum of Natural History, ANT. 28866.

The Lucayans brought ‘javelins’ to trade with Columbus’ men – these may have been spears used in spear fishing or potentially for hunting hutia. None have survived, so it is not clear what they were tipped with, but one possibility is stingray spines, which have been found in the archaeological record. The example illustrated (left) was recovered from the Gordon Hill cave site, Crooked Island. The tip is broken, perhaps from use, and it has clearly been filed down at its terminal end, most likely to secure it to a shaft.

Spindle and Whorl

Image credit: Two whorls, Long Island, courtesy National Museum of Natural History, A554662, A554675. Spindle, courtesy Jamaica National Heritage Trust.

Spindles (long slender wood shafts) and whorls (perforated discs) are combined to make an essential tool in the spinning of cotton.The two worked together to add momentum to the spinning of the cotton fibers into yarn. Only a few whorls have been recovered from The Bahamas, including the two illustrated here – one shell and one ceramic – from Long Island.

Weaving tools

Image credit: weaving tools (2 views each), Pitch Lake, Trinidad. Both ca. 56cm in length. Peter Harris Collection, Pointe-à-Pierre Wild Fowl Trust.

Thin, wooden weaving tools – some with what appear to be handles – have been found at archaeological sites in the Caribbean, such as the two illustrated here from Pitch Lake, Trinidad. These were likely used with looms. The ‘swords’ or beaters – flat, thin pieces of wood – were used to ‘beat’ the weft down to tighten the weave, while wood rods (heddles) would have separated the warps to facilitate the weave.

As the Lucayans wove hammocks, it is likely that they used looms. The style of loom depicted in “The Weavers” is a back-strap loom that continues to be in use in the neighbouring mainland of Middle and South America.