10 Beyond the Everyday

Previous Unit < Unit 10

Beyond the Everyday

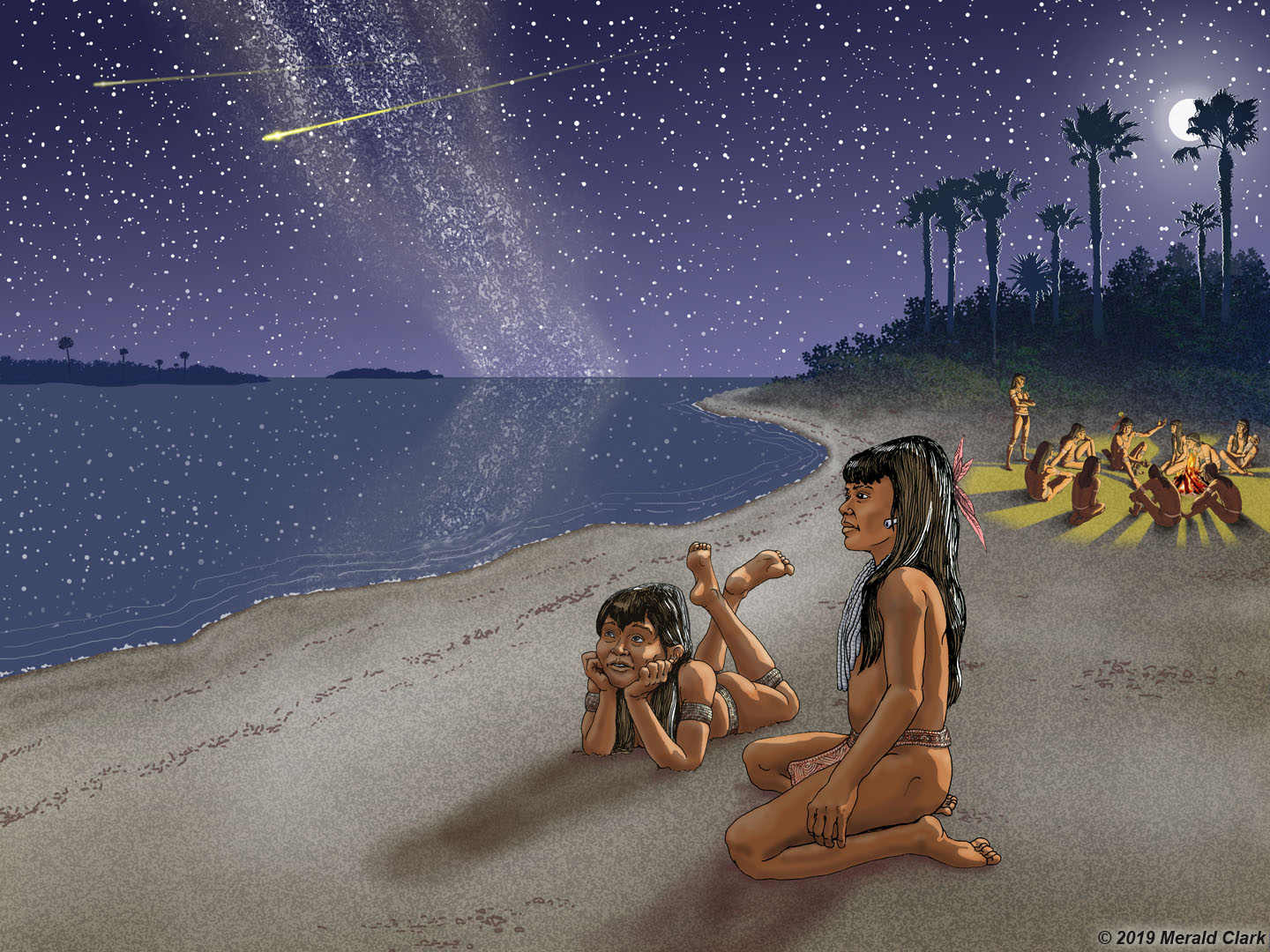

This illustration combines two separate, but linked images: in the background, a seated group listens to the cacique recount a myth, while in the foreground, two young girls contemplate the night sky. They can hear the story even where they sit – and reflect on its meaning as they look out into the bright, starry night. Through the skilful words of the orator, their familiar world – the village, gardens, beach and forest – expands to fill with ancestors, heroes, spirits and supernatural creatures. In a mythic time, these animate forces – through their victories or mistakes, their anger, jealousy, love, or kindness – brought the first people, animals, and plants into being. The girls know that they are still very much present, and continue to create life, but also have the power to take it away. There are rich oral accounts of animals shifting into humans; humans becoming animals, trickster spirits playing pranks on the unwary and causing all manner of mischief. There is much wisdom to the tales, useful in teaching values and morals to each new generation, while also keeping the elders, who heard (and recounted) versions of each story innumerable times, involved and entertained. Through listening to these stories, the girls grow in awareness of their place within the community, and in respect for the wider world – both physical and supernatural – around them.

Lucayan histories, stories and myths

Like many cultures, the Lucayans had rich oral histories and myths. These legends and stories were memorised and recounted, so that each generation learned about the past. The settlement of an island may have been one of these histories – how and why the first people migrated there to live, and the adventures they had in establishing their community. Perhaps a hurricane destroyed one village, or perhaps a man survived a shark attack – these events would have been remembered. Myths telling of the beginning of the world, or the lives of the animals and plants, were also shared. Given their close connections, some myths may have been similar to those recorded for the neighbouring (Taíno/Macorix) communities on Hispaniola (Dominican Republic/Haiti), while others may have been very different – unique to a specific island, or even a village. Unfortunately no Lucayan legends were recorded in early Spanish accounts, or otherwise passed down to us, so we can never know the details of their stories. But it is important to engage with these unknowns; it helps to acknowledge the undoubtedly rich tapestry of their traditions. They, like us today, enjoyed a good story. Stories and legends, however, were not simply a pleasant distraction – they reflected on social mores, and guided on correct conduct.

Histories

The Lucayan language still survives in many island names – Bahama (which translates as ‘Large Upper Midland,’ or today’s Grand Bahama), Bimini (‘The Twins’), Mayaguana (‘Lesser Midwestern Land’) and Guanahani (‘Small Upper Waters Land’ or today’s San Salvador). Early European maps record other names. These names describe the lands encountered by the early migrants into the area, and hint at the possible routes taken by the first settlers from Hispaniola and Cuba.

The influence of legendary Lucayans was felt well beyond Lucayan shores: one of Hispaniola’s most important caciques (chiefs) – Caonabó – was Lucayan. His reign coincided with the arrival of the first Europeans into the Caribbean. Caonabó was principal cacique of the Maguana region (today encompassing the Cibao Mountains of the Dominican Republic), and according to the 16th century historian Bartolomé de Las Casas “belonged to the Lucayo nation… born of the Islands of the Lucayos, who migrated from there to [Hispaniola]. And because he was singled out as a man of war and peace, [he] had become king of that province, and was highly esteemed by all.” He opposed the Spanish presence on the island, and Columbus mentioned him by name in a letter to the King and Queen of Spain, as a ‘very bold’ man who reportedly destroyed the first Spanish fort of Navidad, and would have no qualms in striking any other. He was imprisoned by the Spanish and sent back to Spain to face trial; unfortunately, the ship sank in a hurricane and all on board – including Caonabó – drowned.

Myths

The Taíno and Macorix communities on Hispaniola, contemporaries of the Lucayans, had some of their myths recorded by the Spanish monk Ramon Pané in 1498 (Pané 1999). As the Taíno and the Lucayans had a common ancestral root, it is probable that some of these stories would have been familiar to the Lucayans – but they likely had their own versions that differed in detail, specific to the histories of the people themselves. The Lucayans may have had culture heroes similar to Deminán Caracaracol, one of the quadruplets born to Itiba Cahubaba (‘Ancient Bloodied Woman,’ or Earth Mother) who, together with his brothers, had many adventures that helped create the world. These were primordial times, before the first people emerged. In one tale, through a fortunate accident, Deminán released the ocean and its fish and creatures from a small calabash suspended from the rafters of a house owned by Yaya (‘Supreme Spirit’). The deluge was so great that it filled the world and only the tips of the great mountains remained above the water, creating the islands of the Caribbean.

As they were escaping from the wrath of Yaya, the brothers reached the house of Bayamanaco (‘Grandfather’). Deminán asked whether this grandfather could spare some cassava bread, but instead Bayamanaco spit guanguayo (cohoba-infused spittle) onto Deminán’s back. Cohoba was a hallucinogenic drug that was used ceremonially to seek guidance from the ancestors and spirits. Deminán thus had acquired not the nutritional sustenance of cassava bread, but a portal to the spirit world through cohoba. He returned to his three brothers with the cohoba spittle painfully swelling on his back; it grew to such an extent that Deminán was about to die. But his brothers took a stone axe and cut the swelling open, from which emerged a live, female turtle. The four brothers built a house for the turtle, and married her; their children were the first people.

While we cannot know whether these Hispaniolan myths had parallels in Lucayan belief, there are hints that the Lucayans held caves to be sacred spaces. Many important artefacts were recovered from caves – such as duhos (ceremonial chairs), large wooden platters, stone celts, even canoes and paddles. Rock art has been found in caves – for example, on Rum Cay and East Caicos. Burials, too, were deposited in caves. Some of the most remarkable places for burial were blue holes, which may have been thought of as caves of water. Lucayan burials have been found in blue holes on Andros, Abaco, Grand Bahama and Eleuthera. Caves were entrances to the supernatural world, and hence appropriate places to bury the dead.

Worksheets

Unit 10a: Night Wonders, landscape (JPG, 0.9 MB)

Unit 10b: Storyfire (JPG, 0.9 MB)

Unit 10c: The Storytellers 1 (JPG, 0.8 MB)

Unit 10d: The Storytellers 2 (JPG, 0.8 MB)

Unit 10e: Night Wonders, portrait (JPG, 0.9 MB)